Interview: an overview of child sexual exploitation in Brazil

Luciana Temer, president of the NGO Liberta, talks about the invisibility of this crime and the role of schools for education and reporting abuse

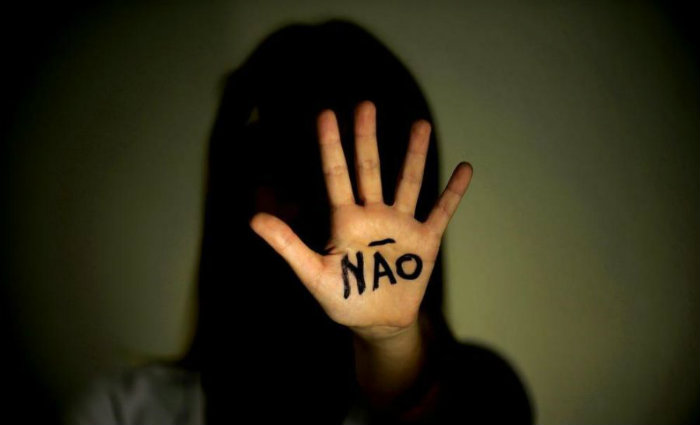

Silhouette of a girl with extended hand on which is written the word “no”.

Silhouette of a girl with extended hand on which is written the word “no”.

In Brazil, May 18 is observed as National Day to Combat Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children and Adolescents – a date to raise visibility on the topic. According to the Ministry of Health, a total of 141,105 cases were registered between 2011 and 2017. Among the victims, 74.2% are girls and 71.2% of the cases occur inside their own homes.

In an interview with Conectas, Luciana Temer, president of the NGO Liberta and law professor at PUC-SP and Uninove universities, explains the social factors that contribute to the continuity of this practice and the myths created around the profile of the aggressors.

Temer, a former women’s defense police officer who has also worked at the São Paulo State Youth, Sport and Leisure Department (2001 to 2002) and the São Paulo Social Development and Assistance Department (2013 to 2016), said schools should play a fundamental role in the discussion on sexuality and gender among children and adolescents and they should also be a place where it is safe to report abuse.

Read more

Read the interview below:

Luciana Temer, president of the NGO Liberta, which works to combat child sexual exploitation

Conectas: Give an overview of child sexual exploitation in Brazil. What factors contribute to the practice of this crime?

Luciana Temer: Brazil is the country with the second most cases of child sexual exploitation in the world and various factors contribute to the practice of this crime. In our society, when people see a girl in a short skirt, for example, they don’t see her as a victim but start to judge violence against her as being somehow deserved. The figure of the victim disappears. This is because we live in a machismo culture, which blames women for violence. Society does not take this problem seriously and does not take action because it does not care. In a survey we carried out with DataFolha in 2018, we found that 72% of people who witnessed the exploitation of 16-year-olds did not report the crime. There is, therefore, a cultural factor.

Conectas: What is the profile of the victim in most cases? And who are the aggressors?

Luciana Temer: One of our jobs is to deconstruct stereotypes. When we talk about aggressors, we are talking about all social classes. They are businessmen, politicians, people from all walks of life. It’s not true that child sexual exploitation is restricted to the North and Northeast regions of the country. The problem is endemic. I often say that it exists in all regions, the only thing that changes is the “price” of the girl and the type of person who “buys” her. The culture of abuse is associated with the machismo culture in our society. The profile of the victim, meanwhile, is usually one of greater social vulnerability. In other words, while there is a wide range of aggressors from all social classes, in most cases the victims are poor and vulnerable girls.

Nevertheless, it is important to raise another point. Another type of child sexual exploitation exists that does not necessarily target the most socially vulnerable girls: it is called “sex extortion”. This is when girls fall into the traps of people on the internet who deal in child pornography. A girl sends a photo of themselves in a bikini, and then the exploiter threatens to release the image if she doesn’t send a nude photo. It is child sexual violence through digital media.

Conectas: What is the difference between abuse and exploitation?

Luciana Temer: There are two categories of crimes that help define these concepts. The Criminal Code uses the term “rape of the vulnerable”, according to which sexual relations with children up to 14 years of age constitutes statutory rape. There is also the crime of sexual exploitation, which is when someone pays to have sex with girls or boys from 14 to 18 years of age. In this case, the payment does not necessarily have to be in cash, it could also be in food, a ride somewhere, a mobile phone or any type of exchange to obtain sex. Conceptually, we cannot talk about child prostitution because children do not prostitute themselves.

Conectas: Why are these crimes considered “invisible”?

Luciana Temer: I am a living example of this invisibility. I used to be the Social Development and Assistance Secretary during the administration of [the then-mayor Fernando] Haddad; for five years I was a women’s defense officer for the police in [the Greater São Paulo municipality of] Osasco; I worked in the Youth Department of Mayor Alckmin’s administration… in spite of this, I never realized the scale of the problem and the consequence of people paying too little attention to it. It was only when I was invited by the Liberta Institute to help combat child sexual exploitation, about four years ago, that I realized how little I actually knew about this topic. It is one thing to know that this type of crime exists, but another thing altogether to be able to rank it and grasp its real scale. While it is still uncomfortable for society to talk about, and while it is not a problem in most people’s lives, the pursuit of solutions will also not be important. Our struggle is to make this crime an issue.

Conectas: Is there a connection between pornography and sexual violence?

Luciana Temer: We need to think about society’s relationship with pornography. Today, the pornography industry is the size of the alcohol and tobacco industry and it is not regulated. This pornography is very violent and places women in a position of submission. Worldwide, one of the most searched for terms on the internet is “teen porn”. There is an entire generation being brought up with pornography. In the past, when a boy became sexually curious, he looked for his father’s Playboy magazine. Nowadays, this child can type into Google “naked woman” or “sex” and he will encounter all manner of free pornography sites. When he grows up, this boy will see his relationship with his girlfriend based on these videos. In schools, boys are beginning to repeat what they see in the videos. If you open pornography sites, you will find films with absurd titles such as “father screws big-butted daughter” or “uncle breaks in hot niece”. In other words, there is an incentive for this practice. People might say that they are just actors and not really father and daughter. It doesn’t matter. The important thing is that it’s unacceptable for just anyone to open a pornography website and have all this available. So I am talking about a change in culture. We cannot have places that encourage this culture, especially when we are talking about a very powerful industry like this.

Conectas: How important is sex education at school in combating child sexual exploitation and how has the Non-Partisan School movement affected this agenda?

Luciana Temer: We put a lot of importance on schools. If we build schools as places for shaping citizens, we will have a privileged space for discussing sexuality, gender and choosing the right paths. Any law that restricts the possibility of free discussion [like the Non-Partisan School movement preaches] is extremely damaging. Especially because, according to the Ministry of Health, more than 70% of sexual violence occurs inside the home. A safe space is needed where children can ask for help. In our view, the school is that space. Sometimes a trigger is needed for a child to come forward. When that happens, they have a place to report abuse.