Descriminaliza STF: why it is necessary to decriminalise possession of drugs for personal use

The discussion about decriminalisation in the Supreme Federal Court started in 2015, but was suspended because of a request for examination of the case by Minister Teori Zavascki, who died in 2017.

Rafael Braga, a young black favela-dweller who used to be a waste picker, was the only person convicted as a result of arrests made at the June 2013 demonstrations. He was caught with sealed bottles of disinfectant and bleach, under the allegation that he was in possession of explosive materials. This led to him becoming a symbol of arbitrary imprisonment in Brazil.

The symbol was further reinforced six months later when the police stopped him while he was under partial house arrest and wearing an electronic tag round his ankle. There were no witnesses and he was taken into custody for drug trafficking and for being involved with drug trafficking, after he left his house to visit his mother. At the police station, the former waste picker was presented with 0.6 grams of marijuana, 9.3 grams of cocaine and a firework that the police said were his. Five years on, Braga was acquitted of the crime of being involved with drug trafficking, but is still serving a sentence, under house arrest, for drug trafficking.

“The war on drugs is actually a war on people.” Said the lawyer Rafael Custódio, former representative for Conectas, ITTC (Institute, Land, Labour and Citizenship), Pastoral Carcerária and the Sou da Paz Institute, at the ruling on the decriminalisation of possession of drugs for personal use at the Supreme Federal Court in 2015. “[The war on drugs] is intrinsically the need for the relentless expansion of the state’s punitive power.”

Read more

During his submission, the lawyer cited research that reveals the target of anti-drug sentencing in Brazil – youths, between 18 and 29 years old, black, whose education did not go beyond primary school and who have no criminal record. In addition, in general, the accused is arrested when alone, unarmed and carrying a small quantity of drugs and without any kind of police intelligence work for imprisonment. “In other words, it is empirically proven that in fact, the Brazilian anti-drugs law works as a mechanism for criminalising poverty.” Custódio said. Rafael Braga is just the best known example of this.

The background of voting

STF discussions on decriminalisation started in 2015, but were suspended following a request for examination of the case by the Minister Teori Zavascki, who died in 2017. At the time, three of the eleven ministers had already declared their votes – the Rapporteur Gilmar Mendes, who had voted in favour of decriminalising all kinds of drugs and the Ministers Luiz Edson Fachin and Luís Roberto Barroso who had both voted in favour of decriminalising marijuana.

The debate was to be resumed on 5 June 2019, but following meetings with President Jair Bolsonaro and the President of the Chamber, Rodrigo Maia and the President of the Senate, David Alcolumbre, the leader of the STF, Minister Dias Toffoli decided to remove this discussion from the agenda and did not set a date for it to be resumed.

If it is decided that article 28 of Act 11.343/2006 is unconstitutional, Brazil will be one of the last Latin American countries to cease to treat users as criminals. In the region, Brazil, Suriname and the Guianas are the only countries that treat the possession of drugs for personal use as a crime.

Decriminalisation in South America

The STF debate should not be affected by the Chamber’s bill of law 37, that was passed by the Senate on 15 May and which modifies the National Drugs Policy. But it is meeting with resistance, in that the bill of law put together by the former federal congressman Osmar Terra (current Minister for Citizenship), in 2010 tightens anti-drugs policy, provides for the possibility of detention for up to three months, in detriment to the policy of damage limitation and strengthens therapeutic communities, who will be entitled to tax free public funding, even though violations of religious freedom and forced labour have been reported at several units, as confirmed by the Federal Board of Psychology and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Repudiation notes regarding Osmar Terra’s bill of law were published by around 50 institutions like the Human Rights Commission of the OAB-SP (Sao Paulo Bar Association), the Brazilian Association for Mental Health, the Federal Board of Psychology, the Brazilian Forum on Public Security and the National Pastoral Carcerária.

Clarification of the debate on drugs

Going deeper into the issue, specialists reinforce the need to understand the difference between the terms ‘legalisation’ and ‘decriminalisation’. “The idea of decriminalisation is to remove users from the sphere of criminal law.” Explained Luís Fernando Tófoli, Psychiatrist at Unicamp and a member of the State Board on Public Policy on Drugs in São Paulo, at a meeting with journalists, held by Conectas. “This is not enough, but it is the first, much-needed, step. This opens the way for broader discussion.” Therefore, the idea is not to make the production and sale of drugs legal, like alcohol, tobacco and medication.

According to the lawyer Cristiano Maronna, Executive Secretary at PBPD (The Brazilian Platform for Drugs Policy), one of the current challenges is to clarify the debate. This is complex in a scenario that bans damage limitation (rooted in caring for freedom and respect for autonomy) and makes abstinence the only therapeutic goal. “We have a flat Earth drugs policy, with absolutely no scientific basis. In this case Osmar’s flat Earth.” Said Maronna, referring to Minister Osmar Terra.

A lack of clarification in the debate could have disastrous consequences, according to the lawyer. “Our principal concern is the mass detention of people who use drugs, because we know that that target is a specific one.” Explained Maronna. In his view, the treatment of crack users, using in public, is not the same as that of an “executive who snorts cocaine in his office on Paulista Avenue.”

Percentual de presos por trafico

A PBPD study of the profiles of users assisted by the programme De Braços Abertos (With Open Arms), in Cracolândia, in São Paulo, showed that crack is not the cause, but rather the consequence of exclusion. Or, as the Columbia University Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry, Carl Hart said, in an interview with Drauzio Varella: “Cracolândia doesn’t have much to do with crack. It has to do with a lack of economic opportunity and the discrepancy in education.”

However, the idea defended by conservative sectors of the policy in Brazil, is that country is experiencing a drug epidemic which can be used to justify extreme measures. But this idea has no basis, as proved by the 3rd National Survey on the Brazilian Population’s Use of Drugs, carried out by Fiocruz, that showed that the countrywide figures for crack users, for example, is 208 thousand, less than the 370 thousand recorded in previous years.

The study, requested by the National Secretary on Drugs Policies (Senad), a body that is linked to the Justice Ministry, cost the public coffers R$7 million and was censured by the government and is still embargoed. Minister Osmar Terra stated that he does not trust research by Fiocruz, despite the foundation testifying to its research methodology.

According to anti-prohibition experts, there is an urgent need to treat problematic users within the health system, not the criminal one. For this reason, they are defending the point of view that decriminalisation of all drugs would be more effective than decriminalisation of just one of them, ie marijuana, a point of view supported by Ministers Luiz Edson Fachin and Luís Roberto Barroso.

Criteria and a lack of criteria

Cristiano Maronna also talks about the “complex manoeuvres in interpretation” to justify incrimination for being in possession of drugs. “They say that somebody who is in possession of drugs, even if this is for personal use, is putting public health at risk because this behaviour represents a potential risk of increased consumption that could lead to an epidemic of dependency in society.” He explained.

The problem is that, according to one of the principles of criminal law, in order for someone to be sent to prison their conduct must harm a third person, as in cases of murder or theft, for example. This does not apply to the personal use of drugs, in which the victim and perpetrator are the same person.

There is also the issue of the lack of criteria for judging what is trafficking and what is personal use, which leads to increased imprisonment. A survey by the Sao Paulo government, published in May, showed that in Sao Paulo alone, the number of people sent to prison has more than quadrupled in the last 25 years, reaching 235,775 people, making Brazil the country with the third highest detention rate in the world, behind the United States and China. Justice Ministry and Penitentiary Administration data from 2018, revealed that one third of men and two thirds of women in prison are there for drug trafficking.

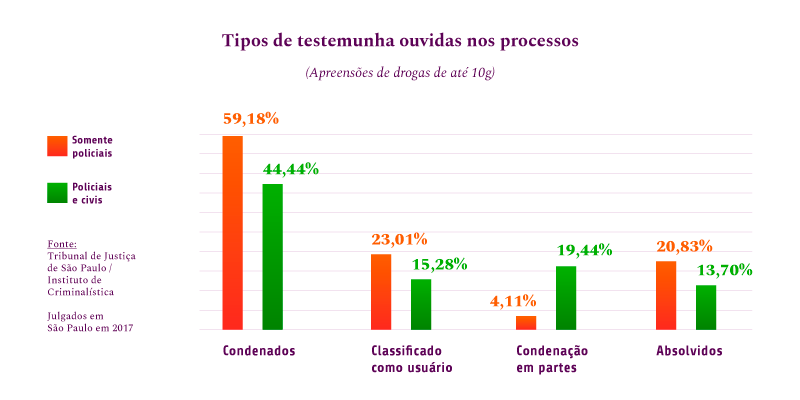

“Criteria and lack of criteria.” Said Maronna. When there is not enough proof for the act of selling drugs, judges usually place greater store on police statements, which Maronna calls the ‘queen of proof’. Research by Agência Pública, that analysed 4 thousand sentences for trafficking in São Paulo, showed that, when up to 10 grams of marijuana, cocaine or crack are seized, in 83.7% of cases the only witnesses heard were the police officers themselves. 59% of convictions were under these conditions, while 44% took place with civil witnesses.

Tipos de testemunha ouvidos no processo

According to research by the Brazilian Jurimetrics Association, since law 11.343, known as the Drugs Act, was created in 2006, introducing a new policy on illicit substances, the proportion of people imprisoned for trafficking jumped from 15.5% in 2007 to 25.5% in 2013.

The lack of objective criteria to define who is a trafficker and who is a user contributes to the high rate of imprisonments. “To be accused on the basis of being either a user or a trafficker is the luck of the draw.” Maronna said. He says that this is why one of the greatest merits of the Drugs Act is to protect the elite and criminalise the poor, which is the best example of how our prison system works badly and selectively.

In the 2015 vote, Minister Barroso stood up for the idea that a person could be in possession of up to 25 grams of marijuana, without being considered to be a trafficker as well as being able to grow a maximum of six plants per user. However, the tendency is for other ministers to decide that fixing criteria is the responsibility of the National Congress.

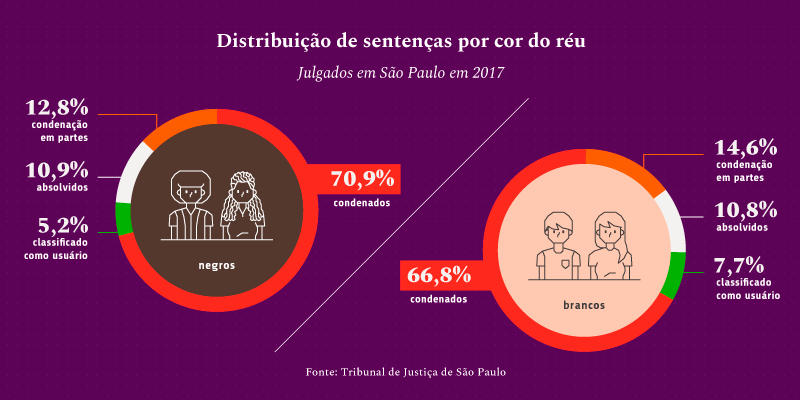

A question of race

Given the lack of clear definition, it is not surprising that the claim made on the basis of the Ministry survey shows that more black people are convicted for trafficking than white people, even though they possess smaller quantities of drugs. “Strictly speaking judges do not judge based on race, but this racist slant and disdain for poverty appear indirectly in sentences.” Said the Psychiatrist Luis Fernando Tófoli.

The Historian, Eduardo Ribeiro, Coordinator at INNPD (Black Initiative for a New Drugs Policy), highlights that there is “racial discrimination contained in words,”, that occurs when, without mentioning the trafficker’s colour, there is an association with black people. “This has a profound impact on STF debates.” He explained.

Ribeiro gives the example of a sentence by Minister Barroso: “Crack changes the equation of the drugs problem because it transforms people into a body without a soul.” “Although he does not talk about black crack users, he is drawing on an idea from the colonial period of black people without souls, the first status of the people captured for slavery.” Ribeiro explained.

The Historian also recalls a declaration made by Cassandra Frederick, at the North American NGO, Drug Policy Alliance, when she said that “white needs drive changes in the law for their own benefit.” “If we look at advances in the debate on access to therapeutic marijuana, for example, we see that this is white people solving their own problems.”

The Historian, Ribeiro recalled other innovations that are not widely discussed, regarding intensification of imprisonment, caused by criminalisation and a lack of objective criteria. One of these is the increase in genetic mapping. In February, the Minister for Justice and Public Security, Sergio Moro, included an increase in the current DNA database on prisoners, in his anti-crime bill of law, increasing the length of time that genetic profiles can be kept, after a sentence has been completed, by 20 years and creating a file with biometric data, with fingerprints and face, iris and voice recognition.

“[Given that the black community suffers more imprisonment] we shall return to the end of the 19th century, when Nina Rodrigues said that black people have a greater propensity for crime. The fact that there are more black people on the genetic database could drive the return of this debate based on a naturalist perspective.” Ribeiro reckons.

According to the Historian, as well failing to prevent the use of illicit substances, which are already widely used, criminalisation destroys black lives and makes generations of children socially accustomed to the language of violence. “When we boycott an entire group of people, from childhood into adult life, we can call this genocide.” He concludes. “Obviously we want article 28 to be recognised as unconstitutional, but we have to know where we want to go from here.” Otherwise, the decision of the STF, even if it is in favour of decriminalisation, will not have any affect at all on the lives of those who are most punished by the law.

#DescriminalizaSTF

With your help, we want to show ministers the urgent need to make progress in drugs policy. Click here and sign the petition to help us to put pressure on the STF to vote for the decriminalisation of drugs.

![]()