Helena Taliberti and Marcela Rodrigues: the pain of loss and the struggle for justice

First-hand accounts with audio excerpts from two women who do not want to let their stories be erased

One year after the social and environmental tragedy in Brumadinho, many families need to cope with the pain of loss while also continuing their struggle for justice.

Helena Taliberti, aged 72, economist and director of the Camila and Luiz Taliberti Institute

Read more

I was in São Paulo. It was a public holiday, the anniversary of the city. I was strolling along Avenida Paulista when I heard about the tragedy through a notification on my mobile phone from one of those news sites. At the time, I didn’t give it much thought. I knew my children were in Brumadinho, but we never think, right… We started getting worried later, when they didn’t reply to our messages.

Then we received the information that we had to go to Belo Horizonte to register them as missing. So we went there to do this registration. After two days without news, we went to Brumadinho. There was no news of them there. Not of my daughter, nor my son, nor my daughter-in-law, nor their father, nor their father’s wife.

There was a place for the families to assemble. It was one of Vale’s facilities and other institutions were there too, like the Civil Defense. There they released, from time to time, a list of the people who had been found and those who were still missing.

I had to do the registration 7 times before their names were included on Vale’s list of missing people. It was a very painful process. They didn’t give us any information.

[click on the paragraph below and listen to the audio]

Look, my life is over, right… How is it that a mother can lose her two children and her daughter-in-law pregnant with her first grandchild? We were thrilled about that, the news of the baby. Camila was at an excellent stage in her life professionally and she was in love… Luiz was in love too, and was doing very well at his job in Australia; he had just been made director at the office where he worked; he had received an award for the second consecutive year; his work had been rewarded. And Fernanda was doing very well, she was really happy with her pregnancy… we were too… what can I say? everything was beautiful, you know, beautiful… and suddenly it all ended… There’s nothing left. There’s nothing left.

[click on the paragraph below and listen to the audio]

It’s difficult to process, difficult to accept… You just can’t bear it. I still keep expecting them to walk in through the front door.

(…)

They never came to us for anything because we’re not from the community, they weren’t Vale employees, they weren’t contractors and they didn’t live in the region.

(…)

We created the Camila and Luiz Taliberti Institute based on my children’s ideals and values. Camila was greatly concerned with social issues and the empowerment of vulnerable groups, especially women. Luiz had an enormous concern for the environment and for quality of life, and so we are following these interests.

(…)

This cannot be forgotten, we need to talk about Minas outside Minas. In Minas, people already know, everyone knows what happened and how things are unfolding, but outside here nobody knows. It has already been forgotten. It’s important for us to speak out and not let anyone interfere because it can’t have been in vain, we need to find a solution so this sector can stop operating in a predatory way like it does now.

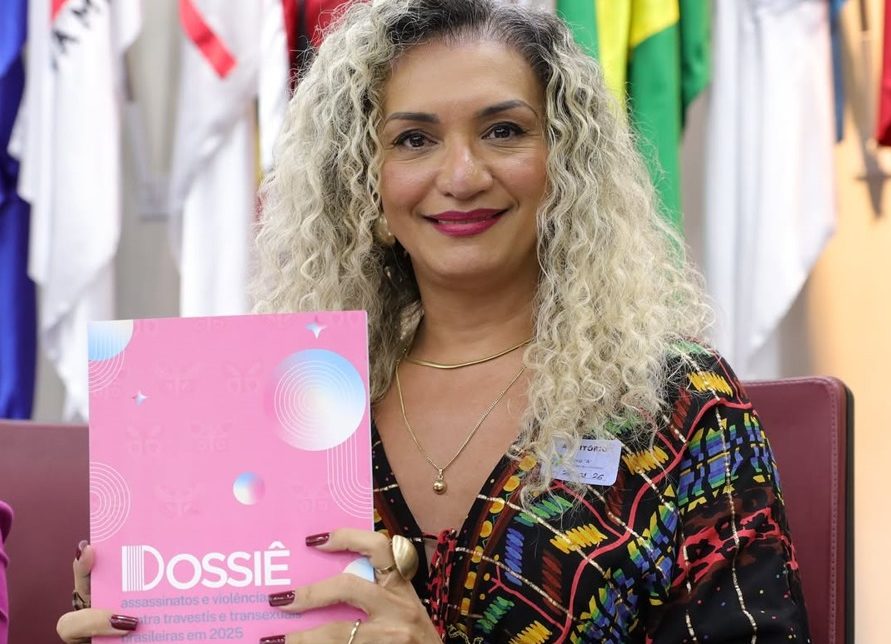

Marcela Rodrigues, aged 26, social coordinator of the Archdiocese of Belo Horizonte who works with affected communities in Brumadinho. She is a student of pedagogy and a local tourism entrepreneur.

I had a hostel in the town, but now it’s closed. On that day, the day of the tragedy, I’d gone on a trip with a family from São Paulo. At about 1 pm, I was on my way back from a restaurant when we saw a flow of people coming down to the reception. There, we received a statement that the dam had burst and they were evacuating everyone because they didn’t know what conditions the town would be in.

(…)

Nobody knew the scale of the incident, the impact that it would really have. As a security measure, the Civil Defense asked all businesses to close.

(…)

The mud didn’t reach the central part of the town, where my business was located.

(…)

I lost my father. He worked at Vale for 17 years, he was 49 years old and worked as an electrical inspector. After that, I broke down emotionally and psychologically, as did most people in the town.

I closed my business. People stopped coming to visit Brumadinho. Tourism here has suffered a lot as a result of the dam collapse, people are afraid of the conditions in the town today, of the contamination.

It broke my family apart, everyone is leaving, nobody wants to relive this pain every day. I still live in the town, I work with the affected communities because I want this number of 272 people to become a landmark, to be a watershed, for there to be a change in this predatory mining system.

(…)

After the dam burst, people started to frequent a place here called the ‘Knowledge Space’, which is one of Vale’s educational projects with sports and educational activities for children. The space had service facilities of the Civil Defense, Vale, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, but nobody knew how to teach anything. The company itself that day didn’t know how to provide news about what had really happened.

We registered people as missing countless times and often the day afterwards, their names still would not appear on the list. We had to go back, we had to go from place to place looking for information.

(…)

Vale offered us lawyers and psychologists. But at the time we didn’t feel confident talking to them, mainly because they defended the criminal position of the company, and what we wanted was a personal service.

(…)

[click on the paragraph below and listen to the audio]

Many farmers lost their land and even though they have received reparations, the money isn’t enough to give them back their livelihood. It takes time to prepare farmland, to get it ready for planting and make a living off it… The disaster put a end to an economic way of life for them. In addition to the mental shock that people are suffering today… there is contamination. The cancer rate has increased, the suicide rate has increased, people are showing up with skin diseases…

(…)

[click on the paragraph below and listen to the audio]

Not only were we, as women, already suffering this stigmatization, this mining company machismo that “implanted” the idea that men work and women stay at home to take care of the children, but I have also noticed that there are now a number of women who are doing very badly because they lost the bedrocks of their homes, they lost the people who sustained them… Unfortunately, most of us believe in this system, that we belong in the home, that we are the women of the home… but I have worked with community leaders and I see the empowerment of women on the front line, in the resolution of conflicts. And so, in this sense, they now have more of a voice.